, May 17, 2006

COLLEGE PARK, Md. - HHOK, I was FOCL.

This may not look like English, but it is

a truncated form that teens are increasingly using to communicate, through

text messaging and instant messaging on phones and computers.

The letters translate to: “Haha, only

kidding, I was falling off my chair laughing.”

Studies show text messaging is changing the way

young people communicate, for

better and worse.

Although phone texting has been praised for

helping teens to connect to each other and to their parents, it

has also been criticized for its potential in making it easier

for teens to cheat on exams or to bully each other with the help

of technology.

It can also eat up time and money.

Mary Madden, a research specialist for the

Pew Internet and Life Project, said 45 percent of teens

have a cell phone and 33 percent of teens send text messages

from their phones.

Of those teens who have cell phones, 64

percent regularly send text messages, according to

the project’s

study on teens and technology, published in July 2005.

Text messaging was not even included in the

Pew Internet and Life Project’s study from 2000, Madden said.

At that point the craze had not yet caught on, she said.

Sherrie Cunningham, a

spokeswoman for Verizon Wireless, said that during the first quarter of 2006, 9.6 billion

text messages were sent or received through its service. Verizon

claims about 60 percent of the country's wireless phone users,

she said.

The figures represent a

huge spike from the 3.6 billion messages sent or received in the first quarter of 2005 and

the

500 million from the first quarter of 2003. The company

launched text messaging as a service in 2000.

Researchers say teenagers are attracted to

text messaging because they want to be in touch with their friends all

the time.

“Being connected to your peers in part of

being a teenager,” said Anastasia Goodstein, founder of

Ypulse.com, which provides news and commentary about Generation

Y. “Todays teens are hyperconnected 24/7.”

Goodstein is writing a book titled “Totally

Wired,” which she said will be published in early 2007. The book will

focus on the many impacts technology is having on teenagers.

On the plus side, Goodstein said, texting

gives teens a fun way to communicate with their friends and also

gives parents an easier way to contact their children.

But, she added, there is a down side. “I

think [texting] is slightly addictive,” she said. “Teachers and

schools are having a hard time controlling it during school or

class.”

There have been well-publicized incidents of cheating

through text messaging at high schools and universities over the past few

years. In 2003, for instance, six University of Maryland students admitted to

cheating on an accounting exam via text messaging.

Madden said text messaging can also become a burden for some

teens.

“At this point in teens’ lives, there’s so

much emphasis on communicating with friends,” Madden said.

“Now, it’s about posting on Myspace, or responding to texts.”

Sarah Wren, 21, a senior at the University

of Maryland, said that she rarely sits through a whole class

without texting a friend on her cell phone.

“It’s just that class can get boring

sometimes,” Wren said. “Why not kill some time talking to a

friend who is also probably bored in class?”

“I don’t know what I would do without text

messaging,” said Tara Valentine, 19, a sophomore French major at

the University of Maryland. “It’s like my main source of

communication now.”

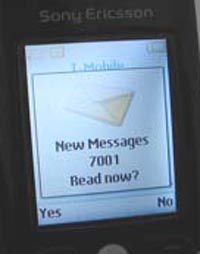

|

| Increased opportunities

for cyberbullying and

cheating are two negative facets to the increase in text

messaging among teens.

(Photo

courtesy Nate Steiner) |

In fact, Verizon Wireless now offers text

messaging for its customers from computers, making it even

easier to connect with friends in different locations.

The message is sent from a computer

directly to the phone of another person.

“Most classrooms have computers in them

now,” Wren said. “So it doesn’t even look like you are sending

a text message.”

Goodstein believes that text messaging is a fun

way for teens to be social but also hears countless stories of

inflated phone bills due to it.

“A teen girl will be fighting with her

boyfriend over text messaging and suddenly has a $200 phone

bill,” Goodstein said. “Parents are getting wise to this

and either saying no to texting or buying unlimited or prepaid

plans,” she said.

According to the Verizon Wireless Web site,

it charges 10 cents for every text message sent or received.

Some of the negative aspects of teens and

text messaging include their ability to

“cyberbully” other students, Goodstein said.

According to cyberbully.org, the term

stands for “sending or posting harmful or cruel text or images

using the Internet or other digital communication devices.”

Nancy Willard, executive director The

Center for Safe and Responsible Internet Use, said that she

believes text messaging among teens has increased bullying. “If you have a cell phone available, it increases the amount of

time you can bully someone,” Willard said.

She has seen this as a growing problem

among teenagers and something that parents cannot take lightly.

“Parents need to have a real serious talk

with their kids about cyberbullying,” Willard said. “They

should say, ‘If you are using your cell phone to bully and I

found out, I’ll take it. GOT IT?’ ”

Willard, 53, who has three children of her

own, two of them teens, also has other worries about the way

teens communicate. “Kids entering college now only know how to

gab, there is no in-depth thinking,” she commented. “It’s all

on the surface level. What are we doing to our kids’ brains?”

Ken Joseph, associate director of the

Media, Self and Society Scholars at the University of Maryland,

said he has seen an increase in the amount of cell phones he

sees in class.

“It’s funny to me because it seems like

students can’t sit through a one-hour class without constantly

looking at their cell phones,” Joseph said. “What did they do

before that?”

But, some say,

increased text messaging does not have to be a bad thing.

“Technology in and of itself is not

positive or negative,” Goodstein said. “It’s how people use

it.”

Copyright © 2006 University of Maryland Philip Merrill

College of Journalism