|

||

Politics

Related Links |

State Touts Teen Smoking Decline, But Numbers Don't Add Up

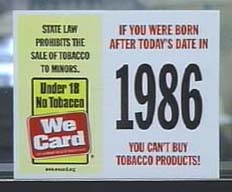

Capital News Service Wednesday, April 28, 2004 ANNAPOLIS - For seven years, Maryland has boasted declining cigarette sales to minors, but a review of state data shows Maryland continues to use questionable tactics known to inflate statistics and make compliance with the law look better than it is. In 2003, Maryland reported that 90 percent of state merchants refused to sell tobacco to minors in unannounced statewide compliance checks. Checks are done as part of the federally-required Synar Report, which tracks states' progress in preventing cigarette sales to minors. For Maryland, $12.8 million in federal tobacco grants hinges on the report and the state's declining figures. This monetary incentive, combined with lax directives on the federal level, can lead to skewed statistics by the states, the U.S. General Accounting Office concluded in 2001. The state's claim of 90 percent is based on 778 compliance checks performed by the state's Alcohol and Drug Abuse Administration from May to August 2002, using supervised underage students who try to buy cigarettes. The state's numbers are suspect for two reasons: Data don't agree with county findings and the state investigates just a tiny percentage of its more than 10,000 cigarette retailers, said Glenn Schneider, a board member for Smokefree Maryland. "It's amazing that so many of our teens report getting tobacco from these retailers and yet (the state) can only find 10 percent (non-compliance)," said Schneider. "It seems awfully strange to me." A survey of 14 health departments performing their own checks showed an average compliance rate of only 81 percent in 2003, with a range of 62 percent to 98 percent. Some counties do no enforcement at all. Several methods yield higher-than-actual numbers, such as using younger participants and employing more males than females. Maryland's checks employ both tactics, and more. Research shows that minors under age 16 are much less successful at obtaining cigarettes at retail establishments, and a small age difference can make a big statistical difference, said the GAO. In Maryland, teens under age 16 were able to buy cigarettes only 1 out of every 10 times in 2001, while 17-year-olds were successful almost 6 of every 10 attempts. Although it knew of this trend, the state slashed the number of stings conducted by 17-year-olds the next year by more than half, from 27.9 percent of all checks to 12.46 percent. That year, the compliance rate rose 11.4 points. Synar officials point out unreleased data from 2004 shows things are getting better, with merchants selling to 17-year-olds much less often than in the past. But when the agency looked into the unusually low numbers, it found that the 17-year-old participant had operated in an area generally known for high compliance rates, said Susan Gray, Maryland Synar project officer. Officials for the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Administration, the state agency charged with collecting the data, say any trend is coincidental. The department hires and trains youth, who can work until they turn 18. Turnover can effect the age and gender of workers, said Donald Hall, with the alcohol administration. All the state's procedures comply with Synar regulations. "We are doing it honestly and fairly," said Hall. "No way are we manipulating the data. We don't juggle our employees to manipulate the results." Federal officials say states have freedom to craft their investigations for a reason. "The truth is, kids who buy cigarettes are all ages and genders and what we hope is that states use a system that is representative of the youth buyers in that state," said Alejandro Arias, public health adviser with SAMSHA, the federal agency that oversees Synar reporting. But Maryland's volunteers aren't representative of the state's youth smokers: While statewide, the typical teenage smoker is about as likely to be female as male, Maryland used girls in just 7.4 percent of the checks in 2001. That number increased in 2002, but still was only 15 percent. Research also shows that females are 11 percent more likely to be sold cigarettes than males, according to the GAO report. Another concern with Maryland's checks is violators get only a citation -- not fines or license revocations -- meaning there's no real penalty for sellers who get caught. Although it's charged with doing the checks, the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Administration doesn't have the authority to enforce them, said Hall. "Here, we would love to be able to enforce Synar. That's not what we're allowed to do," he said. The lax statewide enforcement has spawned numerous county programs, especially since money from the Cigarette Restitution Fund has become available to boost new programs. Enforcement on the county level is varied, both in intensity and style. "Most counties are doing enforcement, but they're at different stages," said Barbara White, coordinator of the Cigarette Restitution Fund program for Carroll County. "It depends on the cooperation between the police department and the health department." Under current state law, only police officers can enforce the no-sales-to-minors statute. But some jurisdictions have enacted local laws to circumvent the issue, allowing health departments or other local boards to do checks. Many even surpass state standards by handing out fines of up to $3,000 for offenses. The rosy prognosis seems far from reality for some jurisdictions, especially in Frederick County, which ranked lowest on compliance of the 14 counties polled. Frederick has one of the most comprehensive programs, and just 62 percent of merchants passed the checks. Officials went out 12 times throughout fiscal year 2003, conducting 143 checks on almost half of the county's licensed merchants. County inspectors say the area has a particular problem with large chain stores: Weis Markets, CVS, Wal-Mart and Rite Aid have all been busted, said Jean Byrd, with Frederick County Substance Abuse Prevention Services. These larger stores, often headquartered out of state, are hard to discipline, said Byrd. Phone trees, discovered by the county's Liquor Board, are another problem, said Byrd. Dealers who have been stung by a compliance check call other merchants in the area to warn them. In Frederick County, inspectors often do checks and return later to cite owners, so they can't warn neighboring stores. The county has cited stores just a day after they passed Synar checks, which highlights another problem, said Byrd: "It's just luck of the draw."

Copyright © 2004 University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism

|