| Maryland Newsline |

| Home Page |

Politics

|

| Baltimore County Man Tracks Down

Forgotten History

By

Sonia Kumar CATONSVILLE, Md. – Louis Diggs was teaching students at Catonsville High School how to research their roots when he realized they weren’t coming up with anything, because nothing relevant was written where they could find it. History books, he says, have left out African-Americans and their role in Baltimore. “They don’t say there wasn’t any, or there were any. They just don’t say anything at all about it.” Diggs’first book, “It All Started on Winters Lane,” thus began as a project to help those kids discover the richness of their heritage. “I really wanted something for the kids, the African-American kids,

to prove that we as African-Americans did have a little bit of something

to say about Catonsville,” Diggs says. “After all, we are due our

history.”

The cover of Diggs'

second

book, which includes the histories of Bond Avenue and

Piney Grove. (Courtesy Louis Diggs)

Since that first book was published in 1995, Diggs

has spent much of his time researching and writing books about several of the 40

historically African-American settlements in Baltimore County. He has

written three more books: "Holding On To Their Heritage," "In Our

Voices" and "Since the Beginning." He is working on his fifth. Along with the narratives he

gathers through interviews, Diggs has amassed an enormous

collection of historical photographs that grace the pages of his books. He

also lectures and conducts workshops in genealogy research to all sorts of

audiences throughout the Baltimore area.

Diggs

says the enthusiasm of the children who read his books keeps him going, as

do the tidbits of fascinating history he uncovers from interviews and old

documents: that Thurgood Marshall’s legal career began with Margaret

Williams vs. the Baltimore County Board of Education, in a petition on

behalf of Williams, who was fighting to attend her neighborhood Catonsville

High School instead of a black

school in Baltimore; that a Pizza Hut and Midas Muffler on Route 40 sit on

a paved-over black cemetery; that Rolling Road owes its name to slaves.

The slaves rolled barrels of tobacco over the old Indian trail

down to ships on the Potomac River in Elkridge.

Margaret Wilson's father hired Thurgood Marshall in 1935

to try to register Margaret and another classmate at the all-white high school in Catonsville. (Courtesy Louis Diggs)

The

stories pour out of Diggs, who doesn't have a single page of notes in

front of him.

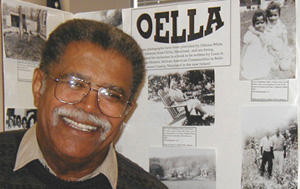

He

cuts an impressive figure, tall and broad-shouldered, but gentle and

mild-mannered. His voice is warm and gravelly, well-suited to oration.

He’s got a touch of a drawl and the long o’s typical of a Baltimorean

accent. In Diggs' mouth "I'm" sounds like "Ah'm" and "out" sounds like "owte."

His

conversations tend to end with the words "thank you now."

At 69, Diggs has retired twice already, and both times he hasn’t been able

to stay retired. In 1970, he retired from the U.S. Army after serving for

more than 20 years. That didn't last, and he began working as a military

instructor at Ballou High School in Washington, D.C.--retiring from the

D.C. Public School system in 1989.

It was after his second retirement that

Diggs volunteered to teach students at Catonsville High School how to

research their roots. He also realized that he wanted to collect information about his

own family’s history for his children and grandchildren.

“I’m a

father, and a grandfather, and I know one day my kids or grandkids will

want to know something about their family heritage,” he says.

'You

Can't Change History, But You Should Know About It'

Diggs

tries to keep his work from inciting tempers, a difficult task considering

the controversy inherent in the stories he has to tell – of slavery, the

legacy of racial inequality, heroes ignored for the color of their skin,

illegitimate children, segregation.

“I tell kids when I mention these things that there’s no need to get angry

about it. You cannot change history,” Diggs says, “but you should know

about it.” Sometimes Diggs has a hard time getting older

African-Americans to open up to him.

"They don't like to talk about it," he says,

"because it hurts."

Diggs

himself recalls drinking from water fountains marked "Colored

only," and using the back door to enter restaurants when Baltimore

was still segregated. When he talks about his own experiences as a

student, Diggs remains calm, although frustration flares out in the

occasional word or phrase.

“When

I was in school, they said that after slavery, people in the black

community were lazy, shiftless, didn’t contribute anything to anything.

That really bothered me,” Diggs says. During the course of the past

decade, this has been a theme that he has sought to refute, and he has

done so successfully, documenting scores of initiatives that originated in

the black communities of Baltimore.

Diggs

describes how working black men pooled together their money to create the

Catonsville Cooperative Corp. in the late 1800s, which was responsible for

creating an amusement park with a religious theme, Greenwood Electric

Park, that many of Diggs' interviewees still remember today.

Kristi Alexander,

executive director of the Baltimore County Historical Society, says Diggs' work is important to the entire

community. His focus on African-American history in Maryland "provides an area of

researched history untapped until now," she says.

Diggs

does everything from researching to laying out the books he writes. When he

decides to write about a community, he begins by looking for a central

place to begin his research. Usually, he will turn to churches or

community centers and approach elderly members to set up interviews and

make arrangements to reproduce their photos. Diggs says he prefers people

who are around 80 years old, although for each community he interviews one

younger person (40 or 50 years old, preferably a family historian)

for a "younger perspective of the community."

Once

he has begun, Diggs spends his time interviewing, transcribing, scanning

photos and writing.

It

All Started on Dewey Avenue

Diggs' great-grandfather, John Eli Diggs. He was born in Piney Grove,

in Boring, Md.

(Courtesy Louis Diggs)

To

echo the title of Diggs’ first book, it all started on Dewey Avenue in

the Hoes Heights area in Baltimore. Diggs was born there April 13, 1932, to

George and Agrada Diggs. He dropped out of Douglass High School in 1950--having completed only the 10th grade--to join the all-black Maryland National Guard. He earned his GED in

Korea, where he fought from 1950 to 1952.

After

returning from Korea, Diggs met Shirley Washington. The two tried to elope

the night before Diggs was shipped out to Germany, but a snowstorm

kept them from making it to Elkton. Diggs wrote Shirley letters every day

until he returned and the two married. In 1957, Diggs was appointed

sergeant major of the ROTC detachment at Morgan State College, and he and

his wife began raising children. Seven years later, the Diggs family moved

to Germany, where Diggs was stationed for three years.

When

they returned to the United States, the Diggses moved to Catonsville and built a home on Arunah Avenue, two blocks off

Winters Lane, where Diggs and his wife have lived since 1979. Over

the years, Diggs earned an associate's degree from Catonsville Community

College (1976), a bachelor's degree from the University of Baltimore

(1979), and a master's of public administration, also from the University

of Baltimore (1982). He did post-graduate work at George Washington

University.

Diggs,

who has four sons and nine grandchildren, says his family has been

supportive of his efforts to document local African-American history. He's

hoping that eventually his son Terry will maintain the work he's already

done, if he doesn't have an interest in adding to it.

"He's doing a

beautiful thing," Shirley Diggs says of her husband's work. She says

she isn't bothered by the amount of time he devotes to his work; she

thinks it's good for him to keep a schedule and stay active. "He gets

up every morning at 4:30 or 5," she says. "I call it his

second job." She adds his work has brought the family closer

together: Their sons have helped Diggs to create his own Web page and covers

for his books and to resolve computer problems.

"I

truly truly believe in what I'm doing," Diggs says. "I'm deeply

concerned that our youth, the youth of the future, will not know our

history in these small communities." Diggs was so concerned that he

founded the Black Writers Guild of Maryland as a support system for

African-American writers; the group was awarded nonprofit status last

year. Diggs plans on applying for a $100,000 grant from the National

Endowment for Arts to help people in other areas who want to document the

history of their communities.

"It's

so needed," Diggs says, shaking his head. "African-American

children need to know our history."

Copyright © 2001 University of Maryland College of

Journalism. Text and limited photos available, with permission and credit,

for use by Capital News Service clients.

|