|

Baltimore Researcher Spends Days,

Nights Looking for Ways to Stop Spread of Deadly Virus

|

|

|

Dr. Tim Fouts, an associate

professor at the Institute of Human Virology (Newsline photo by Nikole Albowicz)

|

Nikole Albowicz

Maryland Newsline

Thursday, May 8, 2003

BALTIMORE - Dr. Tim Fouts is proof that the field of AIDS research is not

for the weak. "You can't be afraid of failure," he says.

Working with HIV vaccines, the assistant professor at the Institute of

Human Virology is familiar with the tribulations of

the job.

But recently, he has gotten a glimpse of success.

Fouts and a team of researchers at the institute have produced a new HIV vaccine "candidate," which has not

yet been tested in humans.

In the lab, the vaccine candidate has proven effective

against multiple strains of HIV.

The Vaccine Candidate

The HIV vaccine candidate produces antibodies that attack and

neutralize the virus before it can infect cells. The vaccine is made from a protein taken from the virus’ DNA. The protein mimics one of the steps

that HIV performs to enter a cell.

When the vaccine is administered, the body thinks it is under attack by the

virus and begins to produce antibodies

to destroy the foreign invader. As with the hepatitis vaccine, in which a series of shots are given

over several months to build up the antibody response, multiple doses of

the HIV vaccine are given to create a certain level of antibodies.

Currently, the vaccine has only been tested on rabbits in the lab. Fouts says what really matters is whether the vaccine will also work in

humans.

He and colleagues are preparing data from the lab experiments to present

to the Food and Drug Administration in hopes that it will approve a clinical trial.

AIDS advocates are hopeful. Scott Brawley, director of public policy for AIDS Action, a D.C.-based

advocacy

group, praised the researchers' work as "an advance over anything we've seen so

far."

If the FDA approves clinical trials for the candidate, it would move

into phase I, which is known as the "safety" phase, Fouts says. During this stage, the vaccine

would be tested on five to 10 human volunteers. The volunteers would be

inoculated with the vaccine and then, like the rabbits, their blood would be

tested at different intervals to see if they produce an

immune response. Their overall health would also be monitored during and

after the trial.

It's uncertain whether the vaccine will be approved for clinical trials.

"The percentage of companies that make it through the pre-clinical phase and

are approved for clinical trials is very small," says Paul Richards, public

affairs specialist for the FDA.

Fouts acknowledged that he and his team face a challenge to win FDA approval.

"My pride will be taking this into clinicals," Fouts says. "It will be even

better if it works."

Ready, Waiting for This Day

It appears that

Fouts, 38, has been preparing for this day since he started working with

vaccines as a doctoral

student at the University of Maryland at Baltimore. He went there after

earning his bachelor's degree in biochemistry and nutrition from Virginia

Tech and after completing a two-year stint as a research assistant in the Division of

Microbiology at the FDA.

At the University of Maryland, Fouts studied the structure of the HIV

envelope. But he became intrigued by bacterial

vaccines after hearing another researcher give a talk about salmonella and its

use in vaccines.

Fouts then began working on how the two concepts could be used together

in vaccine design.

After graduating with a Ph.D. in microbiology and immunology in 1994, he did

his post-doctorate work in New York at the Aaron Diamond Research Center,

where he continued to research the role of vaccine structure.

Then a call came from the Institute of Human Virology in 1997 offering Fouts

a job. While at the institute, Fouts completed a second

round of post-doctorate work and was promoted to assistant

professor.

|

|

|

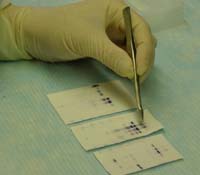

Kathryn Bobb, a research

assistant in Fouts' lab, examines Western blots to find out which

proteins are being produced for use in microbicides. (Newsline

photo by Nikole Albowicz)

|

Now, Fouts spends his time studying vaccines and writing research grants. He also researches vaginal microbicides, products that can be used during

vaginal or anal intercourse to prevent HIV infection.

"Tim is a very intelligent, imaginative and inquisitive person with many

thought-provoking ideas that help keep our creative juices flowing,"

says Dr. Tony DeVico, an associated professor at the institute who works with

Fouts. "He is not afraid to think outside the box."

Loving the Job, Despite Flaws

But Fouts acknowledges that there are a few drawbacks to being an AIDS researcher.

"There's a lot of crap - politics - just like in everything else,"

he says. "It's just the reality of doing business."

Married with children, the Columbia, Md., resident says his work doesn't

allow him much time with his family. He usually arrives

at the institute at 8 a.m. and leaves 10 hours later.

Fouts says he gets to spend about three hours each night with his two sons

and wife before he does more work until about 1 a.m. On the

weekends, he works another eight to 10 hours.

"I don't stop thinking about it," he says of his work.

But even with the long hours and no guarantee of success, Fouts says he loves being a researcher.

"You know where your priorities are," he says. "I believe what I'm working

on will make a big impact in the world, and I will focus on that."

Copyright ©

2003 University

of Maryland Philip Merrill College of Journalism

Top

of Page | Home

Page

|