Scientists Warn of Smith Island's Demise,

Residents Are Skeptical

Waterways wind along the shorelines of Ewell, one of three small communities on Smith Island. (Photo by Maryland Newsline’s Ben Giles)

View Smith Island in a larger map

Retired waterman Eddie Evans, 72, ttraces his family's history on the island back 13 generations. (Photo by Maryland Newsline’s Ben Giles)

Wednesday, April 21, 2010

SMITH ISLAND, Md. - Capt. Larry Laird ferries passengers and cargo to and from Smith Island twice a day, each time navigating the narrow channel that grants passage to his boat through the shallow Chesapeake Bay waters.

A wrong turn to the left or right, and he'll run his vessel aground.

Shallow waters are part of daily life on Smith Island, the last inhabited island on Maryland's Chesapeake Bay that isn't connected to the mainland by roads.

For generations, the water has been the source of the island residents' livelihood, providing crab in one season and oyster in another.

But now, erosion and rising sea levels in the Chesapeake threaten the island's existence.

"In the worst-case scenarios, Smith Island could be gone in, let's say by 2025, 2030 or so," said Raghu Murtugudde, professor at the University of Maryland's Earth System Science Interdisciplinary Center.

"In the best-case scenario, if we slow everything down, if we took a lot of mitigating actions for reducing global warming, then it could go for another 50 years."

The residents of Smith Island, a mostly older generation of retired

watermen, are aware of the environmental threats the island faces, but many remain skeptical of the island's outright demise.

"I'm 72 years old, and the same thing was said when I was a little boy: 'We're gonna be under in 50 years,'" said Eddie Evans, a retired Smith Island waterman. "Now they've added another 50 on."

The island has lost nearly 3,300 acres of wetlands in the last 150 years, according to a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers report, as erosion has wiped out many of the natural barriers and submerged vegetation that protected its shorelines.

Erosion is exacerbated by rising sea levels in the bay, the result of global warming. Globally, increasing temperatures have caused sea levels to rise at about 1.8 mm a year. Sea levels in the bay are rising at twice that rate -- well over 3 mm a year, scientists say.

At the same time, the land in the Chesapeake Bay region is sinking, a phenomenon known as post-glacial subsidence. In essence, the land is settling after thousands of years of continental shifts. This accelerates the rate of sea-level rise.

This dramatic rise increases the size and destructive power of waves and storm surges that harm the island's shores and vegetation.

While residents and researchers differ on the potential damage erosion may cause, many agree not enough is being done to prevent it.

In the past decade, projects to protect Smith Island have been proposed and approved, but only a few have been completed.

Among them was a bulkhead constructed by the Corps in 2002 on the shoreline of Tylerton, one of the three towns on the island.

History as Salvation?

The likeliest impetus for Smith Island's salvation is its history and uniquely preserved culture.

It doesn't necessarily feel like 2010 on the island, "but it is," said Bill Phillips, who's planning a full-time move to Smith Island within the next year. "Some of the customs remain from the old ways, and that's very nice."

The earliest recorded instance of settlers on Smith Island dates back to 1686, and many current residents can trace their ancestry back to two original families: the Evanses and the Tylers.

Eddie Evans has traced his family back 13 generations, when families farmed the fertile island land.

Centuries of erosion forced residents to start fishing and crabbing.

Now Smith Island is in fact many small islands and marshes comprising 8,000 acres, 900 of which are inhabitable, according to the Bay Journal.

A series of waterways separating the islands, which the watermen call "ditches" and "guts," are now large enough for boats to sail through. The waterways connect the island's three towns: Ewell and Rhodes Point on one island, and Tylerton on another.

Each town has a church, a cemetery and a few dozen homes scattered near the docks, where watermen fix crab pots in the winter and bring back catches in the summer.

The few roads are more likely to be traveled by golf cart or bicycle than by car.

At its peak in the early 1900s, about 800 people called Smith Island home. Around 210 people still live there year-round today, with more residents leaving the island every year, according to several residents.

The average age on the island in 2000 was 50, according to Census data. Most are retired watermen who've watched their children and grandchildren move off the island for easier work and better lives.

Only 12 children attend school on the island in Ewell, with kindergarten through eighth grade housed in one building. Fewer students take the ferry to Crisfield each morning to attend high school.

"The native Smith Islanders is dying off," said Evans.

"We're getting people that's coming here in the summer homes, and people that's moving in from other places that just like the lifestyle, but native Smith Islanders is a dying breed."

Changes Can't Be Denied

While skeptical of scientists' predictions of demise, the residents don't deny that Smith Island is changing.

Some have had to move from one home to another on the island, abandoning places where the water has crept up on the land.

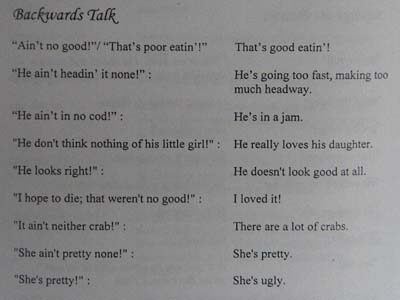

Visitors to Smith Island are often thrown off by the unique dialect and colloquialisms of the residents. Compare Smith Island expressions (left) to the more common mainlanders'. (Photo by Maryland Newsline’s Zettler Clay)

And it seems to be getting worse.

"I've seen tide get in the school twice," said Michelle Bradshaw, a native who's worked as the school janitor in Ewell for 30 years. "And that's happened in the past 10 years."

Measures have been taken to promote the island's history. The Smith Island Cake, featuring eight to 15 thin layers filled with frosting, was named Maryland's state dessert in 2008. The recently opened Smith Island Center provides a history lesson for an increasing number of tourists who come to see the last island.

By raising awareness, some hope they can prove the island is worth saving.

"If somebody puts a value on Smith Island, then obviously engineering solutions are possible," said Murtugudde, the University of Maryland professor. "But we do have to remember that something like the post-glacial subsidence, where our entire continent in this region is going down, cannot be stopped. That's a natural phenomenon."

Some islanders, who have witnessed the decades-long decline of their island's population, are realistic about their own futures.

"The only thing you really can do is whatever you can to break the waves and the swells from coming in here and tearing apart the land," said New Yorker Patrick DelDuco, whose family owns property on the island. "You won't be able to hold it back forever, but something can help."

For others, reasons for saving it are paramount.

"Cause it's home," Evans said. "It's very hard for me to put it in words, to explain that, how that would be to somebody that don't have that same thing that they can call home for that long.

"It becomes a part of you."