|

Family Can't Move on Without 'Missing

Piece'

|

|

Army

Specialist Jason C. Ford was killed in Iraq after his

convoy encountered a roadside bomb in March 2004. (Photo courtesy of U.S.

Army)

|

By Danny Conklin

Maryland Newsline

Thursday, April 28, 2005

BOWIE, Md. -

Florence Newell was able to celebrate her birthday this year knowing

that her ďbabyĒ was back home. On her birthday a year ago, on March 23, 2004, she

buried her youngest child, Army Specialist Jason C. Ford.

Ford, 21, was killed March 13, 2004, in Tikrit, Iraq, after his convoy

encountered a roadside bomb. It killed him instantly, according to

Army media relations. Ford had been in Iraq for just four weeks.

Newell said she misses him so much.

"I miss his hugs. He would run up on me and say, 'Hi Mommy!' " she said.

Even when he was 21, he would still call her mommy, Newell said.

But Ford was always showing affection and concern for friends and

family, Newell and others said. Helping others or acting as a

role model came natural to Ford, they said. Sister Yolonda Smith-McRae

described him as a "born leader."

Family First

Friend

Tiera Jarman remembers when Ford told his nephew, Anthony Smith-McRae,

to go pick out any birthday present he wanted for himself.

"He asked me to go to the mall so Anthony could pick out whatever he

wants, and he picked out this sweat suit," Jarman recalled. Ford

didn't have much, but he was willing to give away what he had to those

dear to him, she said.

Family members all seem to remember the 21-year-old former church

choir drummer as a selfless individual.

Ford, whose parents divorced when he was in grade school, spent much

of his childhood growing up in the District of Columbia with his

mother. The youngest of Newellís five children, Ford had a large,

extended family that he spent time with.

He attended Shaw Junior High School in the District, where he indulged

his passion for music. Playing the snare drum in the schoolís marching

band, Ford found something he truly loved.

"When

he playedÖhe was in another world," sister Smith-McRae recalled.

Every Sunday he played drums for the choir at Paramount Baptist

Church. Jarman said his playing made everyone exclaim, "Hallelujah!"

Ford moved from Washington, D.C., in 2000, to live with Smith-McRaeís

family in Bowie. The decision was made in hopes of giving Ford better

opportunities in life, his mom and sister said.

In Bowie, Smith-McRae remembers the local kids looking up to Ford as

an "older brother." He organized pick-up sports games and neighborhood

clean-ups.

He attended Bowie High School through his junior year, but withdrew

before graduation. Newell said he had trouble adjusting to the new

school environment.

"He was never accustomed to a 'now' crowd; he was a homebody," Newell

said.

|

|

Jason Ford at the

Place de la Concorde in Paris, France, with fellow

soldiers in November 2002.

(Photo courtesy of Yolonda

Smith-McRae.)

| Instead, Ford received his General Equivalency Diploma and enrolled in

the U.S. Job Corps. He started thinking about a career in the

military.

After talking to his friend Jarman, who is currently stationed in

Iraq, Ford decided that the military was right for him. He made the

decision to enroll at the end of 2000, but didnít tell his family,

knowing they would worry, his mother and others said.

"I was upset because he didnít tell me, because I would have tried to

prevent it," Newell said.

In the

end, Ford saw the military as a springboard to a career in law

enforcement.

"His dad is a retired D.C. police officer, his brother is a Prince

Georgeís County police officer, so he sort of had it in his blood,"

Smith-McRae said.

Newell said Fordís goal was to eventually become a military police

officer.

Off to War

|

|

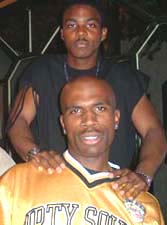

Jason

Ford (standing) with Sgt. Shawn Jackson. Jackson would

accompany Ford's body back to the United States. Ford

was buried at

Arlington National Cemetery.

(Photo courtesy of

Yolonda Smith-McRae) |

Jarman remembers the night before Ford was headed to boot camp, in

February 2002.

"He was playing Psalm 13 [on his stereo] when he found out he was

leaving. He was just sad, and he said, ĎI want to thank you for being

there for me, for being my angel,' " Jarman recalled.

When Ford came back from Fort Benning, Ga., in July 2002, a change was

noticeable.

"I could tell by the discipline. He would get up and run every day.

His whole demeanor, his whole persona was different," Smith-McRae

said. "He was just like, Iím so mature. You could look at him and tell

he was more confident."

"He

was very intense," Jarman recalled.

In August 2002, Ford was given his orders and placed in the 1st

Battalion, 18th Infantry Regiment based in Schweinfurt, Germany.

In

late 2003 news came that he would be going to Tikrit, Iraq,

Smith-McRae said. Ford expressed his reservations on his personal Web

site by writing, ďI will be going to war soon with one of the worst

countries in the world. I will be on the front line watching any and

everything a person could only have nightmares about and I will be

facing it in first person view. Do I have a choice? No, and I don't

know if I will come back."

On Feb. 12, 2004, he arrived in Iraq, and friends who talked to him

could sense his uneasiness.

"I could sense he was very nervous, very scared," Jarman said, after

talking to him by telephone during his first weeks there. "He was

always telling me about having [his] ducks in a row."

On March 13, 2004, Fordís convoy came

under attack while on patrol outside Tikrit, when an improvised

explosive device detonated, killing him and another soldier, according

to Army media relations. He sustained internal injuries from shrapnel,

Smith-McRae said the family was told.

The News

A car with two uniformed officers pulled up in front of his motherís

house around 10 a.m. on March 13, 2004, awaking her from a nap. "I

knew he wasnít coming back," Newell said.

Newell called Fordís father, Joseph Ford, to tell him the news before the

officers got to his house. Then she called Smith-McRae. Newell reached

her daughterís husband, who then called Smith-McRae on her cell phone.

"I asked whatís wrong with my mother?," Smith-McRae recalled. "[He

said] nothing. Whatís wrong with my grandmother? [He said] nothing.

"[He said] itís Jason, and I almost swerved off the road," she said.

"I was screaming and crying."

Fordís funeral was held March 23, 2004, at Paramount Baptist Church.

The place where he spent his childhood making people take notice of

him for his musical ability was now honoring him as a hero.

Trying to Move

On

Newell has been doing what she can to keep herself busy for the

last year.

Sheís thrown herself into her work as an administrative assistant at

Webb Elementary School in the District. She said the children help her

get through the day.

Newell, who still wears her sonís dog tags from Iraq, knows that she

hasnít dealt with his death.

"I donít want to deal with it. Talking about his life makes me happy,"

said Newell. "Heís sort of the missing piece of the puzzle, and with a

family as tight as ours, this has hit us hard."

Francine Harley, Fordís other sister, said she writes about her

brother often for the classes sheís enrolled in at the University of

the District of Columbia because it helps her keep his memory alive.

"He lived for every moment," said Harley. "It didnít matter who you

were, he would come right up and talk to you."

Newell said she uses Fordís life as an example for the kids she helps

at Webb Elementary.

"Take advantage of the time you have," Newell said. "You have to help

people and make use of your life."

Copyright ©

2005 University of Maryland Philip Merrill College of

Journalism

Top of Page | Home Page

|